- Home

- Joan Jonker

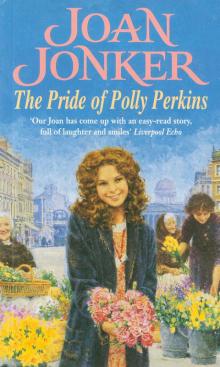

The Pride of Polly Perkins Page 10

The Pride of Polly Perkins Read online

Page 10

‘Not so fast, young feller me lad!’ Dolly chucked him under the chin. ‘Yer mam’s goin’ to sit down an’ have a nice cup of tea.’

‘No thanks, Dolly, I’m stoppin’ Les from readin’ the paper. Thanks all the same, but I won’t bother yer.’

‘Oh, I’m not askin’ yer, girl, I’m tellin’ yer!’ Dolly looked determined. ‘An’ yer’ll find out why as soon as I’ve brewed up.’

Ada shrugged her shoulders as Dolly made for the kitchen. ‘I’m sorry, Les, but I’m not about to argue with your wife ’cos she’s bigger than me.’

‘I don’t blame yer, she throws a hefty punch. I should know ’cos she’s landed one on me many a time.’ Les pointed to a chair. ‘Sit yerself down, girl, an’ tell us how Tommy is.’

‘He’s just about the same, Les,’ Ada said, choosing her words with care because she could feel her son’s eyes on her. ‘No better an’ no worse. It’s goin’ to be a long haul, I’m afraid.’

‘As long as he gets better, girl, that’s the main thing. He’s only a young man an’ when he does come home he’ll be as right as rain.’

Dolly kicked the kitchen door wide with her foot. ‘Get that paper off the table, Les Mitchell, an’ clear a space.’ She came through carrying a tray which she set in front of Ada before standing back with a look of triumph on her chubby face. ‘There yer are, Ada Perkins, aren’t I posh!’

Ada smiled. On the tray were three delicate china cups and saucers with a milk jug and sugar basin to match. In white, decorated with pretty pink flowers, the set was very attractive. ‘Oh, they’re lovely, Dolly! Yer shouldn’t be using them for me, keep them for best!’

‘What the ’ell do I want with best cups? All me mates are like me, as common as muck. They wouldn’t know china from mug.’

‘Well, thanks very much, Dolly Mitchell.’ Ada feigned anger. ‘Sunday afternoon an’ I have to come here to be insulted!’ She looked to Les for support. ‘I’m not as common as muck, am I, Les?’

‘Ay, don’t you be gettin’ round my feller, fight yer own battles.’ Dolly folded her arms and hitched up her bosom. ‘I’m gettin’ me own back on yer for sayin’ I was heavy-handed with me crockery. Well, I’m not, yer see! I got those at five o’clock last night, that’s twenty-four hours ago, an’ I haven’t broke one yet. So there!’

Mild-tempered Les muttered, ‘The day’s not over yet.’

‘Ay, I heard that! Don’t be gettin’ cocky with me, throwin’ yer weight around just ’cos we’ve got visitors, Les Mitchell! Ada here won’t stop me from givin’ yer a thick ear if I’ve a mind to.’

‘Will yer stop shoutin’ and pour me tea out?’ Ada grinned, thinking how lonely she’d be without the humour of her neighbour to lift her spirits. ‘I can’t remember the last time I drank out of a china cup.’

Dolly’s body shook with laughter. ‘Well, enjoy it while yer can, girl, ’cos they’ll probably all be smashed to smithereens by tomorrow.’

‘They’re beautiful.’ Ada watched the cup filling with weak tea. ‘Where did yer get them?’

‘Les got them on his round. Some posh, la-di-dah woman said she’d broken some and they were no use to her now as they weren’t a full set.’ Dolly handled the cup and saucer carefully. If she was going to break one it wouldn’t be in front of Ada or she’d never hear the end of it. ‘Pity about some folk, isn’t it? Poor cow, I feel sorry for her.’

Ada reached for the sugar basin only to find it empty. Thinking it wouldn’t hurt her to do without sugar, ’cos more often than not she never had any in her own house, she put the basin down and picked up the milk jug. That was empty too!

Realising she was having her leg pulled, Ada turned to Dolly. Her neighbour was holding her tummy and rocking with silent laughter. ‘Ever been had, girl?’ Dolly’s bosom bounced up and down as her guffaws filled the room. ‘What d’yer expect? A china cup and saucer, an’ sugar an’ milk! Blimey, there’s no pleasin’ some people.’ Still laughing she bent to open the sideboard cupboard and brought forth a tin of condensed milk. She plonked the tin of conny-onny on the table, nudged Ada’s shoulder and said, ‘Get it down yer an’ like it; beggars can’t be choosers.’ Again the room rang with her laughter. ‘That poor bloody cup’s come down in the world, hasn’t it? Probably never had conny-onny in it before, so watch it doesn’t crack with the shock.’

Grinning broadly, Ada looked on the tray for a spoon. ‘What am I supposed to use for the conny-onny?’

‘Yer could use yer finger, but I suppose I’d better get yer a spoon or yer’ll be tellin’ the neighbours I’ve got lovely new cups but bloody awful manners.’

‘Every dog knows its own tricks best, Dolly.’ Ada watched her open a drawer in the sideboard and chuckled when things started getting flung out in her search for a spoon. Scarf, gloves, braces, a pair of socks and an odd lisle stocking were plonked on top of the sideboard, along with a few choice swearwords.

‘Ah, here we are, I knew I ’ad one in there.’ After wiping the spoon on the corner of her pinny, Dolly handed it to Ada with a flourish. ‘I’m sorry it’s not silver, but I pawned me best canteen last week.’

‘Ha, ha, very funny.’ Ada stirred her tea. ‘Where’s Steve and Clare?’

‘Your guess is as good as mine, girl. Steve said he was goin’ to the park with ’is mates, but where Clare is, God only knows.’ Like Ada, the Mitchells only had the two children, but there wasn’t such a big age gap between Dolly’s as there was between Polly and Joey. Clare was eleven, only two years younger than Steve. ‘They’ll be in when their bellies are rumbling.’

‘Steve’s big day tomorrow, eh? One more year an’ he’ll be leaving school.’

‘I can’t wait, either. I won’t know I’m born with a few more bob comin’ in every week.’ Dolly looked across at her husband. ‘But we don’t starve, do we, love? You make sure of that.’

‘Just about, Dolly, just about. Times is hard but there’s folk a damn sight worse off than us.’

‘Not much doin’ at the docks, then, Les?’ Ada asked.

‘I got three days in this week, which is better than it has been. But yer get fed up standin’ there every morning hopin’ yer’ll be one of the lucky ones.’ It wasn’t often Les raised his voice, but he did now. ‘It’s a ruddy big fiddle! The gaffers have their favourites an’ the same men get taken on every day. No one can tell me there’s no back-handers given over ’cos it’s as plain as the nose on yer face.’

‘Don’t be gettin’ yerself all het up, love, or yer indigestion will start playin’ yer up,’ Dolly said, trying to calm him down. ‘It’s the same the world over an’ always will be. No matter where yer go it’s not what yer know, but who yer know.’

‘It’s a good job yer’ve got yer other little business, Les,’ Ada said. ‘At least yer’ve got that to fall back on.’

Les gave a wry smile. ‘It’s a case of havin’ to, Ada – that, or go hungry. I can’t say I enjoy it, but it brings in a few bob … an’ some china cups for me dearly beloved.’

Dolly’s bosom was hitched up once again as she preened herself. ‘Did yer hear that, Ada? My feller called me his dearly beloved! Oh, he can be dead romantic when he feels like it, can my Les. The trouble is, he only feels like it every Preston Guild.’

Joey had had enough of grown-up talk by this time. He wanted to go home to see if Polly was there. They could have a game of snakes and ladders before he went to bed. ‘Come on, Mam, let’s go.’ He pulled on her skirt. ‘If Polly’s back, she’ll be hungry.’

That reminded Dolly, and she nodded her head knowingly. ‘Oh, I saw Polly with Irish Mary this mornin’ on me way to Mass. From what Mary said, your daughter did very well yesterday, worked as good as the older women.’ She dropped her banter. ‘She’s a good kid is your Polly, always has been. An’ her few bob will be a big help to yer.’

Ada nodded. What was the use of saying they’d need more than a few bob to survive? If all she ever did was moan she’d soon have doors closing in

her face. People had enough troubles of their own without listening to her whining all the time. ‘I’ll get home an’ see what we’ve got in the house to eat. With bein’ in the fresh air all day, our Polly will be starving hungry.’

‘The rain kept off for her anyway, that’s a blessin’.’ Dolly screwed up her face. ‘Miserable bloody job standin’ outside a cemetery at the best of times, but imagine if it was tippin’ down.’

‘Did yer ever do anythin’ with that coat yer bought off me?’ Les asked, picking up the Sunday paper. ‘Good bit of stuff in that coat. It would be a shame to waste it.’

‘Oh, it’ll not get wasted, no fear of that! I’m goin’ to start unpicking it tonight.’ Ada laughed and pretended to stumble as Joey pulled her along the hall as though it was a matter of life and death. ‘If I make a good job of it I might start takin’ in sewing. Ta-ra for now.’ Standing on the front step, she called in a loud voice, ‘Thanks for the tea in those lovely china cups, Dolly. It was a treat.’

Dolly, who had followed her to the door, grinned. ‘I hope that cow in number four heard yer, give her somethin’ to talk about. While she’s havin’ a go at me she’s leavin’ some other poor bugger alone.’

Polly got in not long after them and she was carrying a bunch of daffodils which she proudly handed to her mother. ‘These are for you, Mam, off Auntie Mary.’

‘That was good of her. We haven’t had flowers in the house for God knows how long.’ Ada admired the bright yellow trumpets which seemed to bring sunshine into the room. ‘How did yer get on?’

‘It wasn’t as good as yesterday, but then Auntie Mary had told me it wouldn’t be. She only had her basket with her, an’ a smaller one for me. I stood on one side of the cemetery gates an’ she stood on the other so we wouldn’t miss anyone. At first I thought it was goin’ to be a waste of time, but we got really busy between two and three and sold out in no time.’

‘Yer Auntie Mary knows the tricks of the trade, sunshine. She wouldn’t bother goin’ if she thought it wasn’t worth it.’

Joey pulled on his sister’s arm. ‘Did yer get any money, our Polly? Can I have a ha’penny for sweets?’

Polly swept him up into her arms and held him tight. ‘I’m sorry, Joey, but I only got a shillin’ an’ our mam needs it to buy bread.’ When he looked crestfallen, she smiled into his face. ‘Next Saturday I’ll give yer a whole penny for yerself.’

The promise did the trick and he smiled back. ‘All for meself?’

‘Scout’s honour.’ She set him down and patted his head before facing her mother. ‘I’m famished, Mam, is there anythin’ to eat?’

‘I’ve got some dripping in, will yer have fried bread? It’s not much, but it’s all there is.’

If Polly was disappointed she didn’t let it show. ‘Yeah, that sounds fine! I’ll make it, Mam, you sit down. Oh, I nearly forgot,’ she delved into her pocket and handed a shilling piece over, ‘me wages.’

‘I feel terrible mean takin’ it off yer after yer’ve been on yer feet all day. Don’t yer want to keep a couple of coppers for yerself?’

Polly shook her head. ‘I don’t need it, Mam, honest. I’ve got the card for Steve, so there’s nothin’ else I want. When I’ve had somethin’ to eat I’ll knock next door an’ give it to him in case I miss him in the morning. It wouldn’t be right to give it to him after school when the day’s nearly over.’

‘Is your Steve in, Auntie Dolly?’

‘Yeah, he’s just finished his tea, love.’ Dolly was about to invite Polly in when she saw the card in her hand and had second thoughts. Steve was at an awkward age; he’d die of embarrassment if he was handed the card in front of the family. ‘I’ll tell him he’s wanted.’

As she walked down the hall Dolly’s mind was going back over the years. It was funny how her son and Polly had been friends since they were nippers. She’d never known them fall out or have a cross word, and that was very unusual for kids. Especially their Steve – he was often in trouble for fighting with other boys in the street. But with Polly he was different. Mind you, it would be hard to fall out with the girl because she was always very pleasant and easy to get along with.

‘Yer body’s wanted, Steve.’ Dolly jerked her thumb. ‘There’s someone at the door for yer.’

Steve looked up from one of the comic books his dad had picked up on his round. ‘Who is it?’

‘Never mind who it is! Get that big backside off the chair an’ go and see for yerself.’

‘I’m not goin’ out to play whoever it is.’ Steve stood up and put the comic on his chair. ‘They can go an’ get lost.’

Dolly smiled but didn’t enlighten him. ‘Go an’ tell them yerself. Do yer own dirty work.’

Steve was muttering as he went down the hall. He’d soon get rid of whoever it was and get back to the exciting fight that was going on between the goody and the baddy in the comic. But when he saw Polly his face lit up. ‘Me mam didn’t say it was you.’

‘I’ve brought yer birthday card.’ Polly handed the card over. ‘I hope yer have a happy birthday.’

‘Thanks, Polly!’ Steve tore at the envelope, took out the card and opened it. When he saw the three kisses Polly had put under her signature he blushed to the roots of his hair. He hadn’t put kisses on his card when it was her birthday, he’d just put his name. And this card was nice and clean; he remembered his had dirty fingermarks all over it. Still, boys weren’t expected to be soppy, not like girls. He pushed the card back in the envelope, wondering what to do with it. If his mam saw the kisses she’d pull his leg soft and he’d never hear the end of it. But he wasn’t going to tear it up, not a card from Polly, so he’d just have to find a hiding place. ‘Me mam said yer’ve been out sellin’ flowers with Irish Mary. How did yer get on?’

‘Oh, yer’d never believe yesterday, Steve, it was brilliant! D’yer feel like comin’ for a walk for ten minutes an’ I’ll tell yer all about it?’

‘Yeah, okay!’ Steve still had the card in his hand and nowhere to put it. ‘Hang on till I tell me mam.’ He took the stairs two at a time, pushed the card under his pillow, opened a drawer in the tallboy and took something out, then ran down to the living room. ‘I’m goin’ out for a few minutes with Polly. Don’t touch my comic, Clare, or I’ll belt yer one.’

‘Who wants to look at yer silly comic?’ Clare’s blue eyes flashed. ‘I’ve got me own book to read, so there!’

‘I’ll see yer. Ta-ra.’ Steve ran down the hall with his mother’s voice ringing in his ears. ‘Half an hour, now, d’yer hear?’

‘Let’s walk down to Parliament Street, that’s not too far.’ Her hands in her pockets, Polly fell into step beside him. ‘Yer won’t believe me when I tell yer about yesterday.’ She was so good at describing everything down to the smallest detail, Steve could see Sarah Jane in his mind’s eye. And when she said the old lady didn’t have a tooth in her head and looked like an Indian squaw, he bent double with laughter. The nice lady who bought the three blooms, the man who purchased all the carnations and gave her a tip, and the woman who didn’t think she wanted a fern until Polly talked her into it … all were described in detail, making the whole scene come alive for Steve.

‘I wish I’d been there,’ he said. ‘I wouldn’t half have enjoyed it.’ Polly gave a little skip to keep up with him. His legs were so long he covered the ground in half the time.

‘You’d love Sarah Jane, she’s dead funny. Perhaps yer can come down one Saturday, just to see, like?’

‘Yeah, I’ll do that.’ Steve grinned. ‘I could just stand there an’ watch yer flog yer guts out.’ His face sobered. ‘I wish I could get a little weekend job meself. I haven’t been to the Saturday matinée for ages ’cos me mam says she can’t afford it.’

‘If yer were workin’ weekends, yer daft thing, then yer still couldn’t go to the matinée.’

‘I could go to the first house one night, get a grown-up to take me in. Yer can do that with a U-certificate picture.’

&nbs

p; Polly stopped when they came to the junction of Parliament Street. ‘We’d better make our way back.’ They turned and began to walk back the way they’d come. Polly was silent for a while, then she said, ‘I give all me money to me mam. She’s havin’ a hard time with me dad bein’ in hospital so I’m tryin’ to help her out.’

Her words caused Steve to feel guilty. ‘Oh, I didn’t mean I’d keep all the money for meself ! No, I’d give at least half to me mam.’

Polly glanced sideways, chewing on the inside of her lip. She could trust Steve; he wouldn’t repeat anything she told him. ‘If me mam doesn’t get a job soon, we might end up on the streets.’

Steve halted in his tracks. ‘Nah, don’t be daft! Your mam’s got a job, she’ll be able to pay the rent.’

With a wisdom far beyond her years, Polly listed all the things her mother had to pay out for every week. ‘Just the same as your mam, Steve. An’ it’s not just the big things, like rent, food, coal, gas, and the club woman. What about when the gas mantle goes, or we need shoes or clothes? That’s without countin’ bars of soap, Parr’s Aunt Sally or a new mop when the old one falls to pieces … oh, there’s dozens of things! Even with my few bob a week, it’s nowhere near enough.’

Steve scratched his head as he carried on walking. He’d never given a thought to his mam having to fork out for all those things week in week out. She was always laughing and joking, no one would know she had all those worries on her shoulders. Polly had put him to shame.

More to himself than to her, he muttered, ‘Here’s me moanin’ this mornin’ ’cos I had to have dry bread with me boiled egg. No wonder me mam gave me a clip around the ear an’ said I should count meself lucky I had an egg.’

Polly managed a smile. ‘What’s an egg, Steve? Is it one of them things shaped like Humpty Dumpty?’

‘I’m thick, aren’t I?’ Steve kicked a loose stone out of his path. ‘Too busy thinkin’ of havin’ a game of footie in the park, or a game of rounders.’

‘You’re not thick, Steve. It’s just that men don’t see things like women do because they don’t have the worry of runnin’ a home.’

MB09 - You Stole My Heart Away

MB09 - You Stole My Heart Away MB08 - I’ll Be Your Sweetheart

MB08 - I’ll Be Your Sweetheart MB03 - Sweet Rosie O’Grady

MB03 - Sweet Rosie O’Grady Strolling With The One I Love

Strolling With The One I Love The Girl From Number 22

The Girl From Number 22 Dream a Little Dream

Dream a Little Dream Try a Little Tenderness

Try a Little Tenderness Sadie Was A Lady

Sadie Was A Lady MB01 - Stay In Your Own Back Yard

MB01 - Stay In Your Own Back Yard MB04 - Down Our Street

MB04 - Down Our Street Walking My Baby Back Home

Walking My Baby Back Home One Rainy Day

One Rainy Day MB07 - Three Little Words

MB07 - Three Little Words Stay as Sweet as You Are

Stay as Sweet as You Are Taking a Chance on Love

Taking a Chance on Love EG01 - When One Door Closes

EG01 - When One Door Closes Many a Tear has to Fall

Many a Tear has to Fall EG02 - Man of the House

EG02 - Man of the House MB02 - Last Tram To Lime Street

MB02 - Last Tram To Lime Street The Pride of Polly Perkins

The Pride of Polly Perkins EG03 - Home Is Where The Heart Is

EG03 - Home Is Where The Heart Is MB05 - After the Dance is Over

MB05 - After the Dance is Over